Some time around 1884, Oscar Wilde called at the studio of painter Basil Ward to visit with a handsome young man who was sitting for a portrait. When the work was finally completed, Wilde said, "What a pity such a glorious creature should ever grow old." The artist agreed, adding, "How delightful it would be if he could remain exactly as he is, while the portrait aged and withered in his stead." According to Philippe Jullian, this is where Wilde found the inspiration for his only novel,

The Picture of Dorian Gray.

"Years ago, when I was a boy," said Dorian Gray, crushing the flower in his hand, "you met me, flattered me, and taught me to be vain of my good looks. One day you introduced me to a friend of yours, who explained to me the wonder of youth, and you finished a portrait of me that revealed to me the wonder of beauty. In a mad moment that, even now, I don't know whether I regret or not, I made a wish, perhaps you would call it a prayer...."

The first edition of

The Picture of Dorian Gray appeared on 20 June 1890 in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Disappointed with its reception, Wilde revised the novel in 1891, adding a preface (as he calls it) and six new chapters. His preface is an aesthetic manifesto consisting of twenty-four aphorisms, and it answers critics who charged

The Picture of Dorian Gray with being a scandalous and immoral tale. Wilde and others devoted to the philosophy of aestheticism believed that art possesses an intrinsic value and need not possess any other purpose than being beautiful. This attitude was revolutionary in Victorian England, where popular belief held that art was not only a function of morality but also a means of enforcing it. Wilde jabs directly at this belief through the words of one of his characters: "The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame."

The substantially revised and expanded edition was published by Ward, Lock and Bowden in April 1891. The additions included a romantic subplot with an actress called Sibyl Vane, against the objections of her mother and brother, who reappears with a vengeance in one of the later additional chapters, which also filled out the back end of the tale as Dorian's life spiraled out of control. Boni and Liveright later selected the book to be the first published in its Modern Library series.

The things Wilde said in defense of his novel are striking examples of his relentless jabs at hypocrisy, pretense, and boring conventionality:

"An artist, sir, has no ethical sympathies at all. Virtue and wickedness are to him simply what the colours in his palette are to the painter."

"The English public, as a mass, takes no interest in a work of art until it is told that the work in question is immoral."

"As for the mob, I have no desire to be a popular novelist. It is far too easy."

"It is proper that limitations should be placed on action. It is not proper that limitations should be placed on art. To art belongs all things that are and things that are not, and even the editor of a London paper has no right to restrain the freedom of art in the selection of subject-matter."

"The critic has to educate the public; the artist has to educate the critic."

"Your critic has cleared himself of the charge of personal malice... but he has only done so by a tacit admission that he has really no critical instinct about literature and literary work, which, in one who writes about literature, is, I need hardly say, a much graver fault than malice of any kind."

The essence of aestheticism is stated by the character of Lord Henry Wotton:

"People say sometimes that Beauty is only superficial. That may be so. But at least it is not so superficial as Thought. To me, Beauty is the wonder of wonders. It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible."

Lord Henry is the embodiment of Wilde's contempt for bourgeois morality. He speaks almost exclusively in epigrams, designed by Wilde to shock the ethical certainties of the burgeoning middle class. Our favorite:

"But, surely, if one lives merely for one's self, Harry, one pays a terrible price for doing so?" suggested the painter.

"Yes, we are overcharged for everything nowadays."

Lord Henry becomes captivated by Dorian Gray and initiates him into "...the elect to whom beautiful things mean only beauty." He plays the role of the devil to Dorian's Faust, giving him a "poisonous" French novel (unnamed in publication, but refered to in manuscript as

Le Secret de Raoul, by Catulle Sarrazin) in the style of the classic of decadence

À rebours, by Joris-Karl Huysmans. Wilde also replicated the style and substance of that novel in Chapter Eleven. The plot similarities to Goethe's

Faust are emphasized by a woman in the drug dens who refers to Dorian as

"the devil's bargain." And in a nod to

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dorian comments that, despite appearances, each of us has heaven and hell inside him. Because of these and other obeisances, Wilde has often been charged with being a mere accumulator of writing styles and content, borrowing freely from such authors as Balzac, Zola, Stevenson, Poe, and Doyle. His sole novel, however, is but a small piece of his ouevre, and, in terms of modern popularity and readability, it has stood the test of time better than the three novels mentioned above--witness the reference in James Blunt's recent song "Tears and Rain."

An artist called Basil Hayward has been painting Dorian Gray in many guises of myth and legend. One day he decides to paint Dorian as he really is, instead of a representation of art. When finished he is astonished at the beauty he has captured, and by it Dorian comes to love, Narcissus-like, his own beauty. He expresses the wish that his beauty could remain forever unsullied, with the portrait suffering the degeneration of living. Basil, fearful that everyone will see his idolatry, gives the painting to his subject with the condition it never be publicly shown.

Dorian soon begins a romance with Sibyl Vane. Just as quickly he ends it, devastating Sibyl to suicide, and returns home to discover "[t]he portrait had altered." The painting displays "a touch of cruelty in the mouth." He fears the portrait will now teach him to loathe his soul. Just in time does Lord Henry arrive to pull Dorian back to his narcolectic, aesthetic senses.

Wilde composes his tale through a series of parallels and regular foreshadowing. When Sibyl Vane reveals herself no longer the actress Dorian thought she was, he falls out of love with her; when Dorian reveals himself no longer the simple, natural, affectionate, unspoiled creature Basil thought he was, Basil falls out of love with him. Dorian says, "There is something fatal about a portrait." Basil says "Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man's face."

When they first meet, Basil describes the experience as would someone who has fallen in love. He is as obsessed with seeing Dorian every day as will be Sibyl. Basil gives up his art for a supposed reality of beauty he sees embodied in Dorian, just as Sibyl gives up her art for a reality of love. With their arts no longer a buffer against life, they are both eventually destroyed by reality. When Dorian states his belief that he has killed Sibyl (indirectly, by his rejection), it is a foreshadowing of what he will end up doing to Basil.

Basil's whole life changes when he recognizes Dorian's beauty. Yet when Dorian becomes a man who lives only for beauty, Basil is horrified. When he realises the changes in Dorian that his portrait has wrought, Basil says, foreshadowing his fate, "Well, I am punished for that, Dorian--or shall be some day." Basil eventually decides to exhibit the portrait, but Dorian fears everyone will then see the dark deeds weighing upon his soul. The two men part company as if they had been lovers who agree to be friends, thus ending what Basil clearly experienced as a romance.

What we find most enjoyable in the novel is the gothic flavor and the decadent style. The near-constant epigramatic dialogue of Lord Henry keeps up the fast pace Wilde will later perfect in

The Importance of Being Earnest, and tempers the dark tale with biting humor. The atmosphere in setting scenes is thick and the style of Chapter Eleven is luxurious with elaborate obsession. What didn't work so well was the later addition of chapters. These stood out during our reading in marked contrast to the original chapters--for instance, Sibyl Vane's point of view, leaving Dorian out of the scene completely.

Jeffrey Eugenides says

The Picture of Dorian Gray is a novel about the spiritual risks of reading.

For years, Dorian could not free himself from the influence of this book. ... He procured from Paris no less than nine large-paper copies of the first edition, and had them bound in different colours....the whole book seemed to him to contain the story of his own life, written before he had lived it."

Often a reader can tell of a certain book that has changed them, that has held great influence over their thinking, that has drawn them or pushed them into something unexpected and irresistable. Did the mysterious yellow book drive Dorian to unspecified horrors eventually culminating in murder? Or is this a novel about the dichotomy of man's nature? Or is this a novel about the futility of freezing time, of holding back the inevitable ravages of life? Or is this a novel about vanity and its resulting emotional numbness? Or is this a novel about Wilde's personal struggle with homosexuality? Truly it is a combination of all these, which gives it the endurance and resonance it has enjoyed for more than one hundred years.

Fans of Wikipedia might have fun browsing the

Uncyclopedia, which is fully stocked with

quotes from Oscar Wilde.

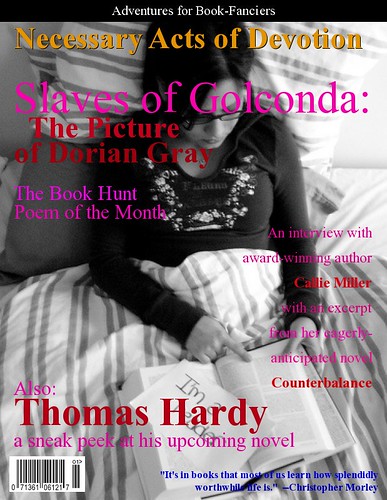

A note about the Slaves of GolcondaColeridge divides readers into four kinds. The first three he believes are to varying degrees lazy, casual, and inattentive. “The fourth,” he says, “is like the slaves in the diamond mines of Golconda, who, casting aside all that is worthless, retain only pure gems.”

The great Bibliogosphere is inhabited by many thoughtful and articulate readers who regularly share their insights on their own blogs. All are after one thing in their reading, and have a compulsion to pursue it. Nearly every day one can find reactions to a literary classic, a new release, a modern romance, a poem, a pop-up book--the variety is endless. The purpose of the Slaves is to gather these readers who toil without recompense in search of the crystalline truth, and all mine the same book at the same time.

Those who participate (see sidebar for a partial list) will be posting their reactions to the assigned book on their own blog, in their own personal style. Bud Parr has graciously invited the Slaves to post at MetaxuCafe as well, with the hope that a centralized discussion may ensue. Comments are welcome whether one has read the assigned book or not.

Registration with the Slaves is not necessary for anyone who would like to read the assigned book and blog about it on the designated day. Nominations for future featured books are encouraged, and will be chosen by the ruling oligarchy and featured on the last day of each month. And if your reading is not as the sand in the hour-glass, or the sponge, or the jelly-bag, then you may truly number yourself among the eminent ranks of the Slaves of Golconda.

on the shelf for a while so we would have the opportunity to read it, and which promptly sold the next day--has a nice clean look with attractive lettering. The art of the lower half of the dust jacket is a form that consistently appeals to us: classic pre-Columbian depictions of life in the New World.

on the shelf for a while so we would have the opportunity to read it, and which promptly sold the next day--has a nice clean look with attractive lettering. The art of the lower half of the dust jacket is a form that consistently appeals to us: classic pre-Columbian depictions of life in the New World. lettering is attractive, especially the alluring "S." The colorful Baroque style is at once heady and decadent.

lettering is attractive, especially the alluring "S." The colorful Baroque style is at once heady and decadent. paintings by the incomparable Vermeer: the titular work, and his "View of Delft" with its famous patch of yellow, "so well painted that it was, if one looked at it by itself, like some priceless specimen of Chinese art, of a beauty that was sufficient in itself...." (from The Captive by Marcel Proust)

paintings by the incomparable Vermeer: the titular work, and his "View of Delft" with its famous patch of yellow, "so well painted that it was, if one looked at it by itself, like some priceless specimen of Chinese art, of a beauty that was sufficient in itself...." (from The Captive by Marcel Proust) white, that conveys a mix of beauty and melancholy, as well as nostalgia for the past. This fiction title is a good example, and similar images can often be found decorating fine biographies.

white, that conveys a mix of beauty and melancholy, as well as nostalgia for the past. This fiction title is a good example, and similar images can often be found decorating fine biographies. looked nice. A beautiful-looking book is certainly a showpiece for any bookshop. We also have a collection of classic paperbacks solely based on the appeal of the cover art. This book was purchased purely for the beauty of its craftsmanship--the clasps give the volume such a romantic aura. We have even acquired books for the look inside, such as the design, the typeface, or especially the margins. Visit

looked nice. A beautiful-looking book is certainly a showpiece for any bookshop. We also have a collection of classic paperbacks solely based on the appeal of the cover art. This book was purchased purely for the beauty of its craftsmanship--the clasps give the volume such a romantic aura. We have even acquired books for the look inside, such as the design, the typeface, or especially the margins. Visit